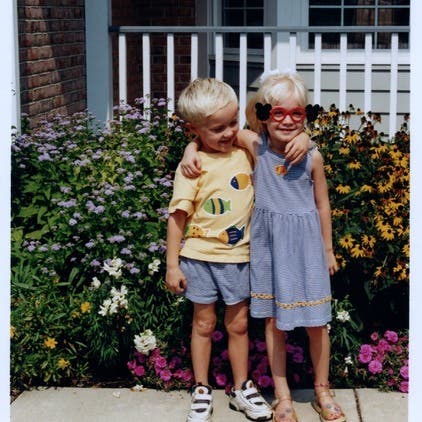

So often in our work with Re:wild Your Campus, we'll have conversations with people that sound like "I care so much about human health and the environment but I don't know how to start" or "Where should I even begin?" To this, I often defer to the wisdom of one of my greatest teachers: my twin brother Michael. Michael's wisdom came not from age, but from circumstance. He was diagnosed with brain cancer when we were ten, lived for four years through cycles of recurrences and recovery. Then, he was given a terminal diagnosis, entered hospice care when we were fourteen, and passed at the age of fifteen. The months he spent in hospice, confronted each day with his nearing mortality, were among the most difficult, yet richest of his and my family's lives together.

For the duration of his short life, Michael had always dreamed of becoming a scientist so he could help people. It hurt him deeply to reckon with the reality that he would not live to fulfill this dream, and he struggled to imagine how his life could make a difference when he was going to die so young.

Now this is the part where I need you to pay close attention... Michael did not give in to despair. He did not resign himself to a terminal cancer diagnosis. He took stock of where he was and what he had to offer with his own individual capabilities and his own timeline. Michael decided that even though he could not become a scientist like he had always hoped, he would donate his body and his diseased tissues to researchers so that they could find a cure and no other child would have to experience what he had endured.

This decision did not happen overnight. Michael spent countless hours thinking, reflecting, grappling with his mortality, and also, with what abilities he still had left. He still had his body to give. He could give up his precious tissue and give doctors a direct look at his type of cancer to better understand the disease, and subsequently, the cure.

This was his wisdom--his ability to reflect, meet himself where he was at, and then act.

It is this wisdom, and the proximity I’ve had to multiple family members with cancer diagnoses– all living within a small radius of each other in an area of the country where conventional agriculture and herbicide-use are widespread– that led me to my work of co-founding Herbicide-Free Campus. I was 19 and Mackenzie was 20 years old when we got to practice at Cal’s beach volleyball courts and were warned to stay off the grass because they had just applied herbicides. Both of our personal experiences prior to this moment led us to ask how we could stop the application of these chemicals. At the time, we were not looking anywhere beyond our courts or beyond ourselves and our own abilities to directly influence the situation. We began just by having a conversation with the grounds manager, in which we asked him if our team could pick the weeds by hand instead of his staff removing them via glyphosate-containing herbicides. And that’s what we did. Only after that success did we have the idea and confidence to move this collaborative working model to the greater campus area, and eventually, to other campuses across the nation. It started with that small, localized step, just as Michael’s decision to donate his body to science started as an organ donation, and ultimately led to his cell lines being used in research labs all over the country.

So, dear reader, if you are confronted by something that you seek to make a change in – finding a cure for childhood cancer, reducing people's exposure to herbicides, building bridges between people with ideas opposed to your own, or whatever it may be – I encourage you to take a page from Michael's book: Stop. Take stock of what you're facing. Look inwards at your abilities, your positionality, and your proximity to the issue. Then, begin. Wherever you are, just begin.

Bridget Gustafson

Senior Strategy Advisor